Jerry Ventre: rocket scientist, solar instructor, and a legend in his (and our) time

By Jane Pulaski

For more than 40 years, Jerry Ventre has been indefatigable when it comes to solar training. Right time, right place, right mind…all the right confluences have kept Jerry as a distinguished leader in the solar training community. It started out so innocently, in the 1970s, teaching a university-wide course on all energy technologies. Somehow that, along with teaching spacecraft design, was the right blend and set him on his long-term solar path. Jerry’s been working with the Solar Instructor Training Network on a variety of tasks, particularly training (what a surprise). He was enormously generous to visit with IREC about where solar training has been, and more importantly, where it’s headed. It was a fortuitous day for solar when Jerry came along. Here’s our conversation.

For more than 40 years, Jerry Ventre has been indefatigable when it comes to solar training. Right time, right place, right mind…all the right confluences have kept Jerry as a distinguished leader in the solar training community. It started out so innocently, in the 1970s, teaching a university-wide course on all energy technologies. Somehow that, along with teaching spacecraft design, was the right blend and set him on his long-term solar path. Jerry’s been working with the Solar Instructor Training Network on a variety of tasks, particularly training (what a surprise). He was enormously generous to visit with IREC about where solar training has been, and more importantly, where it’s headed. It was a fortuitous day for solar when Jerry came along. Here’s our conversation.

IREC: Jerry…let’s start out with a simple question…how did you and solar training find each other?

JV: I got involved not too long after the 1973 Oil Embargo. I was at the University of Central Florida—it was called Florida Technological University at that time, teaching a university-wide course that covered all energy technologies—everything from efficiency, conservation, oil and gas, nuclear, and all the renewable technologies. This course, along with an aerospace engineering course I taught in spacecraft design, got me interested me in solar – both thermal and PV. In late 1977, I joined the Florida Solar Energy Center (FSEC) which was a research arm of the State University System of Florida and is now part of UCF, and helped initiate and teach FSEC’s early courses in solar water heating (PV wasn’t that common back in the late 70’s). Beginning in 1978, solar water heating training was being offered quarterly, and at the same time, we started developing FSEC’s PV program. In 1980, we built a PV house on FSEC’s old campus in Cape Canaveral, complete with a heavily instrumented 5kW utility-interactive system, and offered our first workshop on grid-tied and stand-alone PV applications.

IREC: A pretty busy seven years. Who was the training targeted to? The industry couldn’t have been that large in 1980.

JV: In 1980, there was considerable solar thermal activity in Florida, and the Florida Solar Energy Industries Association (FlaSEIA) was already in existence. However, the industry was really focused on solar water heating, not PV, though there was growing interest in PV. Initially, the training was open to a very broad audience, including the industry, DIY’ers. There was a little bit of interest from the utilities, but in those days they were more concerned about the impact of grid-tied PV on their operations than supportive.

IREC: Good response to the classes?

JV: Really good, yes. But one of the problems back then, as is somewhat the same today, was the diversity of the audience. It’s hard to teach to both a technical audience and a lay audience at the same time without short-changing some of them. It was a good lesson for us in how to better target audiences, establish appropriate prerequisites, and tailor our teaching.

IREC: So did the teaching at FSEC just hum along?

JV: For a couple of years, yes. But for those of us at FSEC, we were highly motivated to upgrade the technical content of the solar curricula. Let me give you a little sidebar here.

Around 1980, there were two PV Residential Experiment Stations—these were funded by DOE and under the technical direction of Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque. One was at MIT, the other was at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces; two entirely different climatic regions: northeast (cold/humid) and southwest (hot/dry). When DOE put out a solicitation for a PV residential station to cover the third climate area—hot/humid, FSEC applied for it, and won the award in 1982. That’s when solar PV training really began to heat up in Florida.

IREC: No pun intended, right? Timing wise, that makes perfect sense—late 70’s, Carter Administration, solar panels on the White House roof. But then came Reagan, and those panels came down, along with the appetite for solar (certainly solar hot water). I’m surprised that DOE was even able to push another PV research station through.

JV: There were periods with different emphasis. From late 70’s to mid 80s, DOE pushed residential, grid-tied applications of solar. But during the Reagan years, as you know, most incentives disappeared. That certainly ended an era of expansion and many solar companies went out of business. During the mid 1980s, the PV ‘Residential’ Experiment stations changed their names to ‘Regional’ Experimental Stations, because without incentives, there wasn’t a market for grid-tied residential PV systems.

IREC: Good thing FSEC had the opportunity to become the third PV experimental research station. What was the game plan once that happened?

JV: It’s interesting how things work out. In addition to solar research, part of FSEC’s mission was education and training–non academic education and training, but it also had a mandate to test and certify all solar equipment manufactured or sold in Florida. It was this combination of the two—the mission and the mandate that helped establish FSEC’s unique training capability. Not only were we exposed to all of the latest solar components, but also we tested them and knew what worked well, what didn’t, and determined how to improve them. The experimental research that we were doing with Sandia and our testing program were major assets that contributed greatly to our training efforts. So beginning in 1982 with the PV Southeast Residential Experiment Station (SERES), that’s when FSEC’s PV training made a giant leap forward.

IREC: I’m guessing there was a lot of collaboration between the three RESs. Did you see an influx of industry folks making the Hajj to FSEC for advanced technical training?

JV: Absolutely. FSEC saw a lot of people during that time, many of whom are still heavily involved in renewables. When Jane Weissman was head of the Massachusetts PV Center, she came to FSEC to observe our design course in 1985. In addition to professionals taking our courses, to broaden the perspectives of our own researchers and instructors, we would send them to other outstanding programs such as those offered by Mark Mrohs (at ARCO Solar at the time) and to Johnny Weiss’ courses at Solar Energy International (SEI). There was a strong, collaborative interest among the existing trainers to share best training practices; it wasn’t competitive. We were all interested in putting together the best programs because we all wanted (and still do) the solar industry to benefit from the best possible training.

IREC: Timing is everything: right place, right time. To which I’d also add, right people.

JV: And right charges and mandates.

IREC: No kidding. So let’s stay with the time line for a minute…what was the solar training picture like in the mid 1980s?

JV: From the mid 1980s to the mid 1990s, the main emphasis for solar was on stand-alone PV systems, including both domestic and international applications. For decades, many stand-alone applications have been economically attractive without the need for any incentives. During that period, training shifted more towards stand-alone systems design, installation, and project implementation.

IREC: Right, that niche market for remote locations.

JV: Absolutely. Conventional grid-power to remote locations was cost prohibitive; many of the remote U.S. locations were in mountainous regions out west. In addition to the remote areas, there were many excellent applications for stand-alone PV lighting, navigation, communications, etc., in populated areas that made excellent sense then and even more today.

IREC: Then the next big shift…the 1990s, during the Clinton Administration, things began to pick up?

JV: Right. In June 1997, President Clinton announced the Million Solar Roofs Initiative which shifted emphasis back to grid-tied residential and small commercial systems. Subsequently, federal, state and utility policies have greatly accelerated grid-tied PV applications. In particular, renewable portfolio standards, investment tax credits and other incentives have encouraged and led to much larger systems. The current trend that we’re seeing now is toward more utility-scale and large commercial PV systems.

IREC: Is that where the training is moving now…to large commercial, utility scale systems? What about industry training?

JV: I think you will see more and more training being offered for large commercial and utility-scale systems. However, it is not clear, at least not to me, what the menu of training options will look like for these large system applications in the coming years. Even though there has been a massive increase in the number of organizations offering PV training programs, most of these programs are still geared toward residential and small commercial systems.

As far as industry-based training is concerned, what I am familiar with is excellent and is primarily intended for company employees and dealers in their marketing and distribution chains. However, industry-based training is usually much more restricted to the specific products supplied by that industry. At FSEC, we’d look at the broad spectrum of modules and inverters supplied by many different manufacturers. This gave course attendees a much broader perspective on equipment and associated performance. In addition to industry-based training, there are lots of other organizations offering solar and renewable energy training today because training can be a lucrative business. Some do it well, others not so much. To find a good, quality training organization requires a lot of due diligence on the part of the potential student.

IREC: Good thing there are options, like IREC ISPQ and the Solar Instructor Training Network (SITN). It’s easy to see how the past 30 years of solar training has, and continues to inform today’s training. How is the SITN widening the scope and impact of solar training?

JV: What we’ve been trying to do over the past several years, and the SITN has really helped with this, is to get needed solar instruction embedded into existing programs at community colleges, universities, and other education and training institutions, so that it’s part of a solidly based program of learning. The three- to six-day intensive short courses are fine for the continuing education of established practitioners and professionals, but they are not foundational and should not be relied upon to build a quality workforce within the solar industry. What we need more of is what Joe Sarubbi did by embedding new PV courses into his two-year electrical construction and maintenance program while he was at Hudson Valley Community College, and what Roger Ebbage at Lane Community College has done with his two-year Energy Management Technician and Renewable Energy Technician programs.

IREC: Absolutely. Both Joe and Roger saw the need and were able to get it implemented in their respective institutions. It seems like a really solid, smart model.

JV: Definitely. It’s important to identify stakeholders, assess their specific needs, and develop programs that meet those needs. In doing so, it is important to account for regional differences in government and utility policies, markets, climate and other environmental conditions.

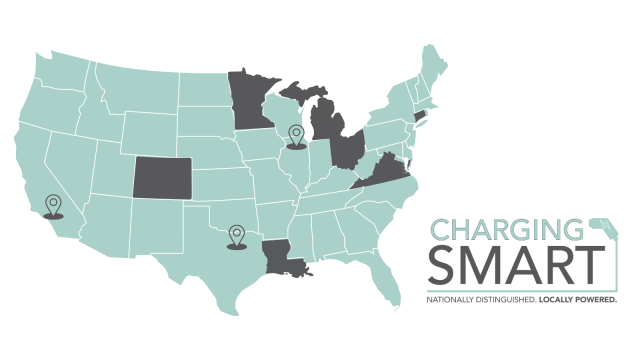

IREC: That sounds like a nice segue to the role of the Regional Training Providers…commonality in training the next generation of trainers, with unique needs and differences.

JV: The RTPs will play a big role, definitely. They certainly have a handle on regional needs and can tailor their training to meet those specific needs. As the new utility-scale and large commercial PV markets expand, one of the challenges for the RTPs is to identify roles that existing solar companies – many of which are relatively small — can play and to adapt their training accordingly.

IREC: How do they do that? This seems like a great time to talk about the recent solar career mapping tool created for the SITN by the brilliant Dr. Sarah White of COWS.

JV: Absolutely. In the solar career map, Sarah (and team) identified 36 different occupations and the kind of training it takes to change jobs and advance within the solar industry. This will help us as trainers to enrich existing programs with courses geared toward PV, solar thermal, and give them a stronger foundation to complement OJT and company-based curriculum.

IREC: We just saw the release of The Solar Foundation’s National Solar Jobs Census (2011) which predicts an overall increase of nearly 7% for solar jobs for the coming year. Is there a demand for solar jobs?

JV: The 2011 National Solar Jobs Census is impressive and shows that many solar companies are seeking to hire qualified candidates with related skills. If we do our job right, we can embed training into existing education and training programs, so you’re not creating a ‘solar only’ specialist. I like to use the IBEW training of electricians as an example for this. Their apprenticeship training is extensive: five-year, 900 hours of classroom instruction, 8,000 hours of supervised and evaluated OJT. Many of the over 300 training centers have already embeded from 40 or 60, to over 100 hours of solar training into their existing training curriculum. They’re still electricians but with the added skills to do solar work when the opportunity presents itself. If we can do this kind of thing—to embed solar instruction into existing education and training programs for other professions, we avoid the problem of training people for jobs that might not exist; we’re giving them more options to enable them to respond to opportunities in the workplace.

IREC: This seems like such a ‘doh.’ Are we closer to this model?

JV: Well, it’s certainly a big push of SITN, working with the RTPs and their partner institutions. Of course, what happens beyond next year is a big question, but if we’re smart, we’ll continue to pursue this model aggressively. We all stand to benefit, ultimately.

IREC: We’ve been talking a lot about onsite, hands-on training. Where’s online training in this?

JV: It’s certainly the trend, driving education in so many ways. It’s a concern because you want to make sure that online programs meet a high standard. Online training has the distinct advantage of allowing students to work at their own pace, giving them time to digest information, to work problems, to practice. It’s in stark contrast to the rushed 8 hours/day, 5 days/week intensive short course. Some of the most innovative training combines online learning with hands-on lab experience, like Johnny Weiss and his team at SEI offers.

Like other forms of instruction, online training can be very good or very bad. Happily, IREC’s ISPQ is helping here by accrediting renewable energy and energy efficiency training programs to a very high standard.

IREC: I know SITN is working on a very large ‘best practices’ resource. With all the brain power behind this task, I suspect this will be one highly sought after resource.

JV: The IREC team developed its predecessor a while ago, but this will be an order of magnitude expansion of what’s available to those who need training assistance. One of the areas, program development, will cover embedding solar content into existing training programs that I mentioned earlier. Another area in the best practices document—one that will be incredibly useful and time saving for trainers—is lab development. Not only will it describe facility and equipment needs for different types of labs, but it will also match lab kits with budget ranges, so trainers can pick and choose what will work for them. And one more piece of that: actual lab exercises completely defined—including learning objectives for each lab session, equipment needed, step-by-step procedures, and data to be recorded and how to analyze it. FSEC did that, and I remember it took an enormous amount of time to develop these things. In addition to the two areas mentioned above, many other areas of best practices will be included in the publication. I’m really excited about this Best Practices document. It’ll be an extremely useful tool for anyone involved in solar training.

IREC: What’s the expression… ‘past performance is no indication of future results?’ Still, when I listen to you talk about where we’ve been and what’s ahead, I’m inclined to be bullish on the future of solar training. Are you pleased with how things have evolved?

JV: I’m really excited about where training is going. The great thing about working in this field is the people we work with. They’re incredibly enthusiastic and passionate about what they do.

IREC: Takes one to know one, I always say, Jerry. With the depth of talent in the field of solar training, it’s heartening. Hurdles lie ahead—we know this, but for the moment, solar training is in incredibly talented hands (like yours). Thanks, Jerry.